Trek to Everest Kangshung East Face Travelogue October 1998

Day 1 September 27, 1998 Arrive in Kathmandu

I looked at the people on the Thai flight from Bangkok to Kathmandu and tried to guess who might be my trek mates. I asked the man who was in the seat next to me, but he was going to Everest Base Camp. As the plane got nearer to Kathmandu, I strained my eyes, and there was Everest, Lhotse and Makalu poking up above the clouds.

The plane flew over the lip of the Kathmandu Valley, low over the eastern part of the city, and then landed at Kathmandu Tribhuvan International Airport. As we turned around to taxi to the terminal, I had a view of Boudhanath in the distance. Because my knapsack was carry-on, I was the first person out the arrivals door. I was met by a local agent for the trekking company. “Please stay here while I pick up the other two people”, he told me. I sat on my knapsack in the late morning warm sun and anxiously waited to meet my trek mates.

The first to come was a woman with short hair. I struck up a quick conversation with her while the agent went back to the arrivals door. I found out her name was Jan, and that she was a single nurse, and had trekked before in Nepal with this trekking company. She seemed like a nice genuine warm person. The second person was another woman with short hair. We jumped in the van and headed to the city. I found out her name was Shane, and that she was a high-school teacher. Her infectious laugh led me to believe we had another pleasant trek mate.

When we arrived at the Everest Hotel, I was surprised to find it was one of the best in the city and even had a beautiful swimming pool. ‘I’d rather be in Thamel’ I said to myself, feeling a little out of place in the opulent setting. “You’re on your own the rest of today. Tomorrow, be ready at nine o’clock for our tour to Boudhanath. We’ll have the trek briefing tomorrow evening at five o’clock”, the agent told us. I asked him about our other trek mates. “There’s three others, ‘he said, “two are already here but are staying at a different hotel, and another flies in tomorrow.” So, that means there’ll be seven of us. Not too big a group, great!

I was sharing a room with another member of the trekking party who had already arrived. I knocked on the door for ten minutes, but there was no answer. I asked the chambermaid to open the door, thinking he wasn’t in the room. She had to find the key, which took her another 20 minutes. When she opened the door, I saw he was in bed asleep. I put down my things, and he slowly opened his eyes. “Oh, hi, my name is Chris, pleased to meet you”, he offered. He had slept so soundly that he hadn’t heard the bangs on the door. He was only 26 years old and was going to start his doctor internship the next year. When he got up, I saw he was tall, well over six-foot and in great physical condition.

I showered and grabbed a three-wheeled scooter to Thamel. I stopped at Helena’s for French Fries and a couple of Pepsis in their garden just off the bustling streets. I browsed through Pilgrim’s bookstore, looking at the multitude of book on mountains and Everest in particular. They even had many copies of Everest: The Kangshung Face, signed by Stephen Venables. I wandered through the streets; saying no to each tout who offered me a shoe shine, Tiger Balm or a pocketknife. I caught another scooter back to the Everest Hotel, where I met up with Chris, Shane, and Jan.

Chris asked us if we wanted to go to Thamel for dinner. We all agreed and got a taxi and got off near the Immigration Office. There was a large crowd of people in the middle of the street looking at a stage with banners that said “Welcome to Thamel - World Tourism Day”. We stopped and listened to the festivities. I could see signs congratulating Ang Rita Sherpa on his 10 Everest summits. I took out my camera to take a photo of this superman. A man who looked like he was in his fifties was at the microphone. He babbled on in Nepali for several minutes, broken by intermittent applause. I could hear the name Ang Rita as he spoke. When he finished, another chubby, short man who looked like he was in his fifties went to the microphone. We were hungry, so I put my camera away and we decided to go on to the restaurant instead of waiting for Ang Rita to show up. Many months later after I was back home in Toronto, I saw a picture of Ang Rita and was shocked to see that HE was that out of shape looking man. I guess looks can be very deceiving. We walked up the street and picked Northfield Café because of its eclectic menu, including Mexican food. We ate and drank beer and laughed as we got to know each other better. We were hitting it off. It looked like my fear of tour groups might not materialize. We went to Pilgrim’s bookstore and I recommended Stephen Venables book to Shane, and she bought it.

Day 2 September 28, 1998 Kathmandu

After one of those all-you-can-eat breakfast buffets the next morning, we met our trek leader, Kumar. He was a short mid-30s Nepali who looked like he was in fantastic shape, with a broad grin and full of self-confidence. He looked like a westerner with his yellow golf shirt, tight black jeans, and running shoes. He quickly escorted us to the bus to go to Boudhanath. I sat next to Kumar and pumped him with questions. Yes, he had done this trek once before. He had been guiding trekking parties for over ten years. He was married with two children, all living in Kathmandu. He boasted about the different treks he led over the years, and how he had almost married a French girl years ago. Although he seemed a bit too cocky, I thought he seemed like a good enough trek leader.

When we got to Boudhanath on the outskirts of Kathmandu, Kumar found a local Tibetan to lead us around the stupa. He told us in his broken English that Boudhanath is the largest stupa in Nepal and one of the largest in the world. It is estimated to be about 1400 years old and is said to contain a fragment of bone from the Buddha's body. The base of the stupa was octagonal, shaped like a mandala, and symbolizes earth. On top of the base is the dome symbolizing water; then the spire symbolizing fire. The all-seeing eyes of Buddha, including a third eye in the middle, stare down from the four sides of the spire. The Buddha’s nose is actually the Nepali number ek or one, which is a symbol of unity and the "one" way to reach enlightenment through Buddha's teachings. The upper part of the spire consists of a stepped pyramid in 13 gilded disks representing the 13 steps to enlightenment. The spire tapers to a gilded umbrella hung with a colorful skirt, representing wind, and finally the pinnacle symbolizes infinite space

With his brief speech over, we were free to wander around and head back to the hotel in an hour. I slowly circumambulated the stupa taking in the atmosphere. Mingling with the local Tibetans, refugees from the Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1959, I turned each prayer wheel as I quietly chanted ‘om mani padme hum’. Each spin of the prayer wheel sends prayers to the heavens - now that’s a lot easier than reciting prayers I thought. Many of the Tibetans carried small hand-held prayer wheels, which they twirled to provide even more merit. Cotton prayer flags connecting the spire to the base sent their prayers on the wind each time they flapped. There were Tibetan shops selling souvenirs, Buddhist gompas, and restaurants and hotels.

To get a better view, I walked through the side streets to a hotel on a small ridge. I politely asked if I could go to the roof for some photos and they pleasantly obliged. I sat there for a while just soaking in this wonderful scene; the size of Boudhanath struck me even more so from this higher farther vantage point. I returned to the entrance to Boudhanath, and looked at the chaotic street scene, which even had a butcher's shop right on the street.

After taking the bus back to the hotel, I once again went to Thamel to savor the smells and sounds of this tourist ghetto. I ate a late lunch at the famous Everest Steak House; a delicious meal of steak, French Fries and a cold beer – delicious. I reluctantly gave up my freedom and returned to the Everest Hotel for our pre-trek briefing.

I sat alone in the huge chandeliered lobby, decadently complete with soft chairs and leafy plants. The first person to show up was one of our guides, named Ram, a 21 year-old brought up just to the south of Makalu in the Arun Valley. He was warm and friendly with a great smile showing perfect white teeth. He told me this was his fifth year as a porter and part-time guide, and that this would be his second time doing the Kangshung Face trek. He sent most of his money back to his mother to help his family survive their struggles as farmers. I instantly like him.

In addition to Shane, Jan and Chris, I met our three other trek mates. “Hello. I’m Gerhardt and this is my girlfriend Valerie.” Gerhardt had a slight hint of a Germanic accent while Valerie seemed British. He looked as old as me with a little gray in his hair, a bit weather-beaten, but looked physically strong. Meanwhile, she looked like a model, nicely thin with a bright red top, sexy black shorts, shoulder length brown hair and nice looking nails.

Ben was the last of our trekking party to arrive. He told me he was a 25-years-old nurse on an extended holiday. He had just come from India, and after this trek planned to take another organized trek with the same company up the Gokyo Valley. He seemed polite and pleasant with a warm hearty laugh. I liked him immediately.

“There’ll be another three guides joining us tomorrow morning; you’ll meet them then”, Kumar told us. Ram brought in our camping kits so we could ensure everything was ok. “Here is your duffel bag; everything that you’re not carrying in your daypack must fit in it. These are your down jackets, and here is your sleeping bag.” Chris and I were on the floor in a minute and snuggled into them. “They seem fine” we both commented.

Kumar then brought out the portable altitude chamber to show us what we’d have to do if one of us suffered extreme altitude sickness. Kumar wanted to demonstrate how it worked, and asked for a volunteer. We looked at each other, all saying no way. So, Kumar got into the bag and lay flat while Ram zipped up the two metre long bag. We could see Kumar’s face through a small see through opening, but I was glad I wasn’t in the bag – it looked too claustrophobic for me, but I guess if you’re really sick it won’t matter. Ram pumped rhythmically and we watched an LED readout show the attitude decrease. I think this gave most of use the willies and we hoped we would never have to use it.

When everything was completed, Kumar commented, “We’re leaving at 7am tomorrow morning, so you should be up for breakfast by 6:30 at the latest. See you then”. The seven of us went to dinner at the Hotel restaurant and hit the sack early. Before bed, I took my first 500mg Diamox tablet to try and stave off the affects of altitude over the next few days.

Day 3 September 29, 1998 Drive from Kathmandu to Nyalam (3750m) in Tibet

I was up at 5:30 the next morning and thoroughly enjoyed my last shower for a couple of weeks. Chris and I were first from our group to arrive at the buffet breakfast. A very tall thin man in his 60s, with bushy eyebrows and a few strands of gray hair on top of his head sat alone at another table. He wore a white short-sleeved shirt criss-crossed with suspenders holding up his blue pants. When Kumar arrived he told us the man had missed his tour group and was hitching a ride with us. He introduced himself as Bill Norton. I chatted briefly with him and found out he was a retired 66 year-old civil servant from London and was part of a British trek to the Kangshung Face which was a day ahead of us. I looked down and noticed he was wearing dress shoes, odd indeed. Later I was to learn he was the middle of three sons by Edward Norton, the British mountaineer on the ill-fated 1924 British Everest Expedition that saw George Mallory and Sandy Irvine mysteriously disappear on the North face. Norton had attained a height of 8572m (28126 feet), an altitude record without oxygen not surpassed until 1978 by Reinhold Messner.

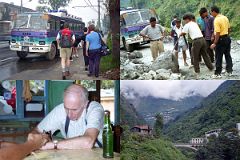

A little after 7 o’clock we strolled through a light sprinkling of rain to our 30-seat light blue and purple Tata bus. Our journey had officially begun! I looked around and waved at the other three guides in the back of the bus. I sat down and looked out the window quietly as the green countryside drifted along in the overcast weather. The road was generally in pretty good shape but an enormous rock blocked one spot. Kumar and the four guides tried to move it, but to no avail. From far up the road I noticed a road worker wearing a yellow hard hat coming towards us. His arm and leg muscles rippled as he used a crow bar to move the rock out of our way.

We arrived at the few lodges making up the Nepalese border post at Kodari (1873m) just before noon. After completing formalities, I gazed up the road to the Friendship Bridge, the true border, and the Chinese town of Zhangmu (2300m) strung along a steep mountainside 11km away with pine trees on all sides.

I had a quick chance to introduce myself to the other three guides.

Rajin was a cool-looking 21 year-old wearing wrap-around sunglasses, a white t-shirt, jean cutoffs, and brown loafers. He told me he was from the low valleys and loved living in Kathmandu and dancing to western pop music. Like Ram, he would be one of our guides.

I then met the ever-smiling Purna, who wore rumpled clothes and looked like he was in his mid-30s. He told me he would be our cook. Chris quickly nicknamed him ‘Anna’, and the rest of the trip we called him (Anna)Purna.

Phurba was in his mid-30s and looked like a very neat looking city slicker with his hair neatly coiffed and wearing a fashionable golf shirt, dark green slacks and black running shoes. He would be the assistant cook.

Our luggage was moved from our bus to a Tata truck, and we climbed in and sat on the luggage to continue our journey. After driving a few metres to the long piece of wood that marked the exit from Nepal, Kumar told us to get out, that we were going to use a different truck instead. Kumar explained that the Chinese insisted on using a Chinese truck to drive to Zhangmu rather than a Nepalese truck. Our truck backed up to the border and our provisions were transferred across the border to the Chinese truck. We jumped in the back and sat on our luggage, joined by three other tourists and a Tibetan family of five including a baby in a pouch on her mother’s back. I stood up at the back of the truck, holding on to the circular frame.

We drove up the road, crossed the bridge and started slowly driving through hairpin turns on an extremely rough track. Every time we lurched left or right, my arms were pulled aggressively. After ten minutes, my arms were extremely sore and I couldn’t wait for this short journey to be over. I held on for dear life and quietly mumbled the mantra ‘Om mani padme hum’ to keep focused on the journey, and not the pain. After thirty minutes, I was extremely relieved to get to the Chinese border post and got out of the truck.

We met our Tibetan guide Tashi, a young 24-year old man carrying a small black briefcase across his red fleece jacket, and wearing brown hiking boots and blue jeans. A couple of men came up to us and asked us to ‘change money’, which we did after Tashi said it was ok.

After a short wait, our three Toyota Land cruisers arrived and we jumped in and ascended the hairpin turns through Zhangmu. We continued to climb out of the lush vegetation into the gray barrenness of the Tibetan plateau on the 30km ride to the small village of Nyalam (3750m). We checked in to the Snow Land Hotel. Nyalam is small, consisting of mostly Chinese buildings situated in a gorge surrounded by gray hills. The seven trekkers, the three drivers, and the five Nepalese all settled down and ate a large Chinese dinner. The official itinerary had us staying in Nyalam for another day to help with acclimatization. I asked Kumar if it was possible for me to trek part way to Shishapangma base camp the next day. Kumar then informed us that he wanted to break the very long journey to Kharta into two days, rather than one. He told us this would also allow us to visit the Pelgyeling Gompa and the famous Milarepa’s cave. This sounded like a good idea, and we all happily agreed. Our first day had been exciting, and I looked forward to continuing the adventure the next day.

Day 4 September 30, 1998 Drive from Nyalam (3750m) to Tingri (4350m)

We had an early breakfast the next morning. Bill looked like he was in bad shape. Ben told us that he had been throwing up all night from altitude sickness. However, when his landcruiser arrived, he jumped in the back and drove off to catch up with his tour group – quite a trooper I thought.

After driving 10km, we stopped and walked down the hill to tour the Pelgyeling Gompa on a terrace overlooking the river. A young monk showed us around the monastery that was rebuilt in the mid 1980s after the Chinese destroyed it in 1966. We walked into the almost completely dark cave where the poet-lama Milarepa (1040-1123) spent many years of his life meditating in his thin cotton robes. His images usually portray him smiling with his hand raised to his ear as he sings. Several young children from the local village ran to see what was going on, and were warmly received by both Shane and Jan. Jan especially entranced the children blowing bubbles with her small bottle of soap. The young girls smiled beautifully with their dirty clothes and long hair, braided and parted in the back reaching down to a small piece of cloth joining the two sides. They each wore two sets of earrings, one blue and the other red dangling down, and a necklace of intermixed stones of blue, red and yellow.

We stopped again after two hours on the top of the Tong La (5124m), a high broad wind-swept brown plateau contrasted with colorful prayer flags. I looked back the way we had come, but the clouds obscured Shishapangma. The road drops briefly from the Tong La and ascends to the Lalung La (5050m). We descended the other side of the pass and had a quick break for lunch. Chris and Jan couldn’t eat and just sat with their heads in their hands from their altitude-induced headaches. We departed quickly and completed our 150km journey to Tingri (4350m, also called Old Tingri), and checked in to the Everest Snow Leopard Guest House Hotel, rectangular in design with a small entrance and an enormous inner courtyard. Our room was decorated in Tibetan colours and had two single beds with heavy blankets and a two-litre light blue coloured Chinese tea thermos. Chris immediately hit the sack to nurse his headache. I offered him some Diamox, but he said he was taking it already.

It had turned bright and warm, so after washing my hair and a few clothes, I just sat taking in the warmth of the sun. Ben came over and was rearing to do some physical activity, so we agreed to hike about two km across the Tingri Plains and climb a small bare brown hill about 500m high. I led and set a fairly fast pace; Ben kept up nicely and had to rest only occasionally. This was my first chance to see Ben in action and he performed very well. When we got to the summit, we looked out on the vast Tingri Plains criss-crossed with small rivers with the houses of Tingri tucked in below a small hill. The headwaters of the Phung Chu (Chu is Tibetan for river) starts here before flowing along the northern perimeter of the Himalayas, bending southward through Kharta, entering Nepal (where it’s called the Arun River) between Makalu and Kanchenjunga, and eventually flowing into the Ganges. You’re supposed to be able to see Everest and Cho Oyu from here on a clear day, but alas it was not to be for us.

We headed back to the hotel and found Chris was feeling a bit better. So, Chris and I walked into the town of Tingri as the sun dropped down in the sky. Surprisingly, it brought out some beauty from the barren plains and hills with the light and shade of long shadows getting more and more yellow/red as sunset approached. I looked back and spotted a nomad camped in the plain before Tingri. The clouds parted briefly and Cho Oyu snuck out to reveal itself at sunset. Beautiful! After a hearty dinner, we slept soundly.

Day 5 October 1, 1998 Drive from Tingri (4350m) over the Pang La (5250m) to Kharta (3690m)

The next day at Tingri dawned clear, so I walked to the highway to watch the sunrise. Sure enough, peaking above the hills was the upper portion of the north face of Everest. At first, I didn’t know if it was Everest, but then with my binoculars I started to make out some of the north face features. I followed the skyline to Gyachung Kang and Cho Oyu fully decked out in their splendid white coats above the brown of the Tingri Plain.

A handsome young teenage boy carrying a Tibetan book under his arm said hello and waved to us as we drove off. Maybe the Chinese occupation is loosening I thought.

We stopped for a few minutes when our truck broke down; then continued for 49km to our turn off for Kharta. About 15 children surrounded us when we stopped at the check post at the small village called Chay. The road, hacked out of the steep boulder strewn hill by the Chinese for their ascent of the North face in 1960, followed a zigzag pattern to the Pang La pass (5250m). The famous view of Everest wasn’t to be, and with the wind and cold we quickly jumped back into our landcruisers.

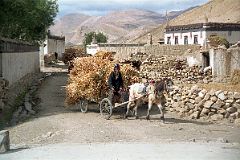

We stopped for a half hour at the Peruche, a small village as the junction of the road to Kharta, to see if our truck was coming. I wandered around taking photos of the local people, still using horse and buggy to transport their provisions. I walked in to the local guesthouse and was quickly offered some Tibetan tea and a seat among the local people and some tea. I sat down and asked for a Pepsi, which I devoured quickly as I watched the local people drink their tea, talk and laugh heartily.

After half an hour, the trucks hadn’t arrived, so we continued on our way, turning left at the junction (we’d see the right hand junction in a few weeks time on our way to the Everest North Face Base Camp) and heading towards Kharta. We stopped for lunch on a grassy field next to the Dzakaa Chu River with plenty of sheep grazing quietly. We watched as a young Tibetan couple led their donkeys past us, followed by a wrinkled old man leading his yaks, probably carrying supplies to market.

Finally, as we packed up to leave, our truck caught up to us. Before long the road was washed out and we had to cross with the half-metre high water flowing quickly by. We’re lucky, Kumar later told us, if it had been a little higher, we’d have had to wait until it lowered. We turned south rejoining the Phung Chu (Arun), traveling high above the river on a rough narrow track; we were lucky we didn’t meet any oncoming traffic. We passed through the village of Kharta (3690m) and left the Phung Chu as it entered a gorge on its way to Nepal. We turned right (west) and entered the Kharta Tsangpo valley with the Kharta Chu on our left. This fast moving river, milky white from glacial meltwater, flows from the Kharta Changri (7056m) and Khartaphu (7227m) mountains to the northeast of Everest. We pulled in to a grassy spot next to the river, a spot already occupied by nine tents.

Some of the other trekkers waved to us, and said hello. From their British accents we guessed that this is the trekking group that Bill had initially missed. Sure enough, out popped Bill to say hello and thank us for getting him to Nyalam. He was in great spirits and told us the altitude sickness had worn off. He told us there were ten in their group and that a mountaineer by the name of Stephen Venables was leading them. I was flabbergasted; Stephen’s description of traveling up this remote valley and climbing the seldom seen east face of Everest in his book was the reason I was here in the first place. I anxiously anticipated meeting him. Stephen’s wish at the end of his Everest climb had come true, as written in his book, “I hoped that I might return one day to this magical valley for a real holiday, with no commitment to high-altitude masochism, free to rock climb and explore and hunt for flowers.”

The British mountaineer George Mallory passed through Kharta in 1921 trying to crack Everest’s defenses. He continued up the Kharta Valley and did find the North Col, which indeed was the secret to the North Face. When he saw the Kangshung Face, he commented: “other men, less wise, might attempt this way if they would, but, emphatically, it is not for us”. It was for Stephen Venables who climbed it in 1988.

Before long, tea was served and Chris and I undid our duffel bags and rested in our tent. We had five a-frame two-person tents: Chris and I, Jan and Shane, Gerhardt and Valerie, Ben, and Kumar. I strolled over and peaked into the kitchen, which consisted of two tents joined together, and was pleasantly surprised at how clean they kept everything. All cooking utensils, pots and pans, and dishes and cutlery were meticulously washed. Pots were soon filled with soup, vegetables and hot water and cooked over two propane stoves. I climbed about a 100 metres up the side of the road to catch the sunset and get my body loosened up. I walked back to the tents in need of using the toilet. Ah, there it is. The toilet was a small, but tall, blue tent with a simple hole dug about 1/4 metre into the ground. I picked up the roll of pink toilet paper and did my business. When I came out, I walked to a rock outside the mess tent and picked up the soap and washed my hands. Everything is very organized, I thought.

I sat on a rock, enjoying the feeling that the trek was about to begin. And then there he was, Stephen was sitting outside his tent carefully cleaning his camera body and lens. I said hello and told him I loved his book. He told me this was his first time back since the climb, and that they were leaving tomorrow. Our too-brief conversation was interrupted by my call to the mess tent.

The large blue mess tent was quite spacious with small metal fold-up chairs for us to sit on and three fold-up tables joined together with a tatty flowery plastic tablecloth on top. This would be the first time the seven of us would be confined with each other. We talked briefly about meeting Stephen Venables, and about his book. Sha mentioned she even got his autograph.

Ram brought in the soup, and we passed it around so we could each serve ourselves in a metal mug. Ram and Rajin then carried in two pots. The first contained vegetables, including my favourite - potatoes, and the other some suspicious canned meat. I was hungry, so I had a heaping helping. The conversation continued with Chris telling stories from his Med School, mainly focusing on bodily functions. We were all soon laughing uproariously at the strange antics of Chris and his fellow students. Shane eagerly shared her crude humour with us, while the rest of us mostly just laughed. Gerhardt and Valerie sat together near the tent opening and stayed fairly quiet, speaking softly to each other.

Kumar came in and outlined our plans for the next day. “The British trekking group is leaving tomorrow and following the exact same route as us. So, we’ll stay here another day, so we don’t have to compete for campsites along the way,” Kumar stated. Kumar did not eat with us. He would eat his dhal bhat (lentils and rice with vegetables) dinner later with the other Nepalese. Ram then brought in cookies and boiling water so we could have tea, coffee or hot chocolate. I declined, but asked for hot water for my water bottle. Everybody else joined in and wanted their water bottles filled too.

With dinner over, I brushed my teeth, used the ‘blue tent’, and went to bed. Although there was a vestibule on the outside of our tent, I put my boots inside at the bottom of my sleeping bag next to my feet. I had read in some books about things being stolen in the middle of the night and wanted to take no chances. I mentioned this to Chris who put his stuff inside too. Within minutes I was asleep.

I woke up around 2am with a feeling I was suffocating with my eyes facing the side of the tent. I sat up and breathed deeply, and looked around the tent. I was feeling a little claustrophobic, so I put on my boots and coat and stood outside. I just stood there for five minutes admiring the stars and breathing the fresh air. I heard a dog barking quite nearby, so I decided to get back in the tent again. I’d read some horror stores about dogs with rabies biting people and the pain and anguish it causes, and I wanted no part of it. I was able to get back to sleep before waking just before dawn. This feeling of suffocating was to happen almost every night while we were trekking.

Day 6 October 2, 1998 Stay at Kharta (3690m)

I got up and put on my clothes and used the ‘blue tent’, washed my hands and walked over to the kitchen tent. Ram was the only one up, getting water boiling. Rajin, Purna, and Phurba were huddled tightly together in their sleeping bag among all the pots and pans and food. Ram said hello and asked if I wanted sweet milk-tea, which I accepted happily.

Ram and Rajin walked to each tent, giving them tea and cookies in bed. After boiling another pot of water, Ram walked back to each tent to offer hot water for washing. Ah, what a life, just like in the old colonial days. I finished my first mug of milk-tea and accepted another mug when Ram had returned. Purna was the next up, and quickly started preparing breakfast.

I entered the mess tent and sat down to see what breakfast would hold. Ram first brought a couple of different cereals, including corn flakes and porridge, and hot milk. The others dug in while I held off for the next course. Rajin and Ram came back with toast, marmalade and jam, and offered us fried eggs. It tasted great. We finished our breakfast with tea and coffee. Kumar came in and told us we were on our own for the rest of the day, and that some sandwiches would be available around noon. He left to work with Tashi to get our Yaks and Tibetan yak herders from the nearby village of Kharta Yeuba. Chris said he just wanted to go back to bed and rest, and Shane and Jan quickly agreed.

I sat outside and watched the British camp being dismantled, put on yaks, and eventually leave. Ben came over full of energy and asked if I’d join him climbing the 1000m hill next to our tents.

There was no track, so we scrambled up a slippery rock slope with small thorny bushes, some green, a few orange. There were occasional tall thin plants with a top covers with small yellow flowers that reminded me of the Giant Lobelia in East Africa. We walked up and up. False summit after false summit made fun of me, and after two hours I gave up - how close I was to the top I’ll never know. I glissaded down the slippery slopes and got back to the mess tent in only forty minutes.

After lunch, Chris, Ben, Shane, Jan, and I decided to walk to the small village of Yulok we could see on a rise across the river. We strolled up the jeep track and after half an hour crossed the river on a log bridge.

We passed through a few houses, which were built by piling rocks upon rocks, in a neat interlocking pattern, and topped with a flat roof with fading branches stacked on top. There were a few small windows and animal horns rested on top of the low wooden door that served as an entrance. On one side of the door was neatly cut stacked wood; on the other was yak dung stacked higher than the door, neatly patted into circular plates, drying in the sun waiting to be used as fuel. We walked across the recently harvested fields, passing shaggy goats and scraggly trees.

Four boys and three girls from the village ran down the hill to stare at us. The boys wore dirty tattered western style clothing, while the girls wore traditional Tibetan clothing, except for their cheap Chinese green sneakers. Chris tried to take their photo, but as soon as he’d get the camera to his eye, they’d run away. This became a running gag with Chris raising his camera and them running away, only to return in another minute. Shane led the entourage of trekkers and children up towards the village. I lagged behind and noticed that the older girl wore an animal hide on her back, connected with small strings to the large metal belt on the front. Her hair was plaited and rolled into a bun at the back with a piece of red and blue cloth. One of the younger girls had a baby wrapped in a cloth on her back.

As we walked through the village we heard a loud bullet-like sound. We veered towards the sound and found a man dressed in all gray from the hat on his head to his feet cracking a whip. He smiled warmly and Chris motioned for him to demonstrate his whipping technique while we took photos. He obliged and laughed heartily as he expertly snapped the whip a couple of times. I patted him on the back as we waved goodbye and started our walk back.

The children followed us all the way back to our camp, staying a couple of metres behind us. When we got back to the camp, Kumar brought out a book with photos and they eagerly crowded around turning each page with anticipation. I walked to the edge of the river, and threw some rocks in the river. One of the boys popped his head up from the book to see what I was doing. I don’t know if this is a common pastime here, but before you know it, he was standing next to me throwing rocks. The rest soon followed and we had a great time splashing the rocks in the river, throwing them across the river, and trying to hit specific boulders that stuck out of the water. As I watched the boys I had a pang of homesickness, wishing my son Peter could be here throwing rocks with us. When it started to get dark, we all waved to each other with broad smiles, and they started their walk back home. The western trekkers had a glimpse of real Tibet while the Tibetan children had a fun distraction for the day.

Day 7 October 3, 1998 Trek from Kharta (3690m) to Dhampu (4300m)

The next morning dawned overcast with low-lying fog and light drizzle. The yak herders were already there with their yaks.

Some of the yaks weren’t actually yaks, but dzos, a cross between a yak and a cow. Yaks are very strong animals, able to carry up to 80kg, and are physiologically suited to high altitude. I watched as the different loads were put together. The lead yak herder lifted each one and spoke to Tashi who told Kumar to redistribute the weight. After fifteen minutes, all was ready. Tashi assigned a small stiff piece of paper to each load, turned around and mixed up the paper, and randomly handed them out to each yak herder. It looked like a great way to ensure fair play.

I didn’t have a raincoat since I hadn’t expected any rain on the trek. The rest of my fellow trekkers quickly put their Gore-Tex jackets and rain ponchos on, while I took a green garbage bag out of my pack, ripped a hole for my arms, and donned my cheap raincoat. It actually worked, keeping me quite dry except for my arms, which were exposed.

Ram led the way as we walked up the valley, the going quite easy. After two hours, he stopped us to have our ‘bag lunch’: a jam sandwich, two hard-boiled eggs, and a few cookies. I don’t think any of us finished this bland lunch. Ram wanted to wait for Kumar to catch up, so we lazed around. Two boys from an unseen village wandered up to see us. We immediately offered them our left over lunches, which they eagerly accepted and put into their small bag. Shane got out her Tibetan phrase book and spoke to them. They were surprised at this foreigner speaking their language and they laughed. We were getting colder and colder from our inactivity, and off we went again. The trek was only slightly more difficult as we turned left and started our ascent towards the Shao La (5030m).

After an hour, Ram stopped us again and we just stood around waiting for Kumar. As soon as Kumar arrived, we asked him to keep going for another hour or two because we had done practically no hiking at all and felt in great shape to do more.

Kumar said no, that this was Dhampu (4300m) and was as far as we were going for the day. He mentioned that we needed to take it easy the first few days to get acclimatized before crossing the high pass.

The seven yaks rounded the corner with their bells tinkling, being led by the six yak herders who also carried some of our things. We crossed a small stream and Ram and crew quickly set up out tents and served us tea and cookies. The Tibetans set their camp just beyond sight of our tent. They set up two wooden poles about ¾ metre high and hung a striped tarpaulin between them. They hung a second piece of material to close the far end and put their provisions there; the other side was open to the elements. I was surprised to see a woman starting the fire with small branches and pieces of wood; she wasn’t with us when we started. She cooked in blackened pots balanced between rocks.

Day 8 October 4, 1998 Trek from Dhampu (4300m) to Lake Camp below Shao La (4700m)

The Tibetan woman was already up starting the fire for their breakfast. She wore the typical Tibetan chuba, a black robe reaching from her shoulders to the top of her flimsy green Chinese sneakers, held together with a wide belt made of multi-coloured cloth on the back and silvery metal on the front, a long dark apron, and bright green long sleeved top. Her hair was braided and held in a bun with a coloured piece of cloth. The other six were still under their blankets beneath the tarp, all huddled close together sleeping head to head crossways.

I had my usual early morning milk-tea while I waited for the others to get up and join me in the mess tent for breakfast. Suddenly I heard Shane cursing profusely. I went over to see what was going on. “Those bastards, they stole my hiking boots, my Gore-Tex jacket, and even my Tibetan phrase book.” She was fuming, and quite rightly so. “I left them in the vestibule of my tent which was zipped up. I can’t believe it. I can’t believe it.”

Kumar and Tashi came over and Shane went through what was stolen. Kumar and Tashi then walked to the other tents to see if anything else was stolen. I told him Chris and I had taken our things inside the tent and didn’t have any problem. Ben said nothing was missing. Gerhardt and Valerie weren’t so lucky; he lost his Gore-Tex jacket while she had her hiking boots stolen.

Tashi and Kumar left to talk to the yak herders, but they’d heard nothing in the night. Kumar walked back to Shane and Valerie and told them it probably was the local villagers, and that nothing could be done. He asked them if we needed to go back to Kharta to try and find new shoes, but luckily both Shane and Valerie had running shoes. (It was good that it wasn’t my hiking boots because I didn’t have anything else to wear on my feet). Tashi told them that they’d be ok with those running shoes, that there was little chance of any snow. So, we would continue our trek a little lighter while the local villagers wore new hiking boots and brand new Gore-Tex jackets, or maybe they’d sell them to get some money to help with their subsistence living.

The sun came out briefly and warmed our jangly nerves. It then started to drizzle again so I offered Shane my other garbage bag to wear over her fleece. She got a better offer from Gerhardt who had more industrial strength garbage bags. We looked like a motley crew as we continued our hike to the Shao La with Shane and Gerhardt wearing matching dark green garbage bags while I fashionably followed in my light green garbage bag.

As I climbed up though the gray rocks I turned around and saw the Tibetan woman coming up behind me, effortlessly carrying a metre high box in a metal carrying container. When we stopped for a rest, she stopped too. Chris tried to take her photo, but she refused. We asked Kumar what was in the box she was carrying, and he told us, “Eggs.” Immediately Chris nicknamed her “The Egg Lady”. Chris used sign language to ask the Egg Lady if he could try lifting her load, and she smiled yes. It must be remembered that Chris is a very tall, very young man in great physical shape (for a westerner). He strained with all his strength but could just barely lift it off the ground, yet alone put it on his back and hike with us.

“Man, that thing weighs a ton; she’s amazingly strong!” Chris said. He smiled back to the Egg Lady acknowledging her prowess.

A Tibetan couple coming down from the Shao La carrying large logs stopped and chatted with one of the our yak herders. They poured some liquid from a plastic container that hung from their logs into a small wooden bowl that hung from their belt and sipped the drink. They offered some to the yak herder who took out his wooden bowl and also drank the suspicious liquid. The Tibetan man offered me some. I asked Rajin what it was.

“It’s rakshi, kind of like whiskey but much stronger.” Rajin replied.

I smiled at the man, but shook my head no thank you, I’d like to live a few more years. We continued climbing and stopped in the early afternoon, setting up camp (4700m) on the shores of a lake just below the Shao La.

Day 9 October 5, 1998 Trek from camp before Shao la (4700m) over the Shao La (5030m) to Joksam (4000m)

The next day we continued our ascent and with the increased difficulty, the relative strengths of the group emerged. Chris was the strongest gliding effortlessly up the slope; I came next a bit slower but maintaining a steady pace. Ben and Shane came next, both keeping a steady pace slightly slower than mine. Gerhardt looked really strong, but walked with Valerie, who seemed to struggle a bit. Jan brought up the rear, struggling and going very slowly. She constantly needed short rests, but her willpower kept her going.

After two to three hours, depending on each person’s speed, we arrived at the chorten identifying the Shao La pass (5030m). The weather was overcast, but occasionally a little bit of blue sky snuck through. Kumar told us we’d have lunch just below the pass, and from there to our camp would only take another one to one and a half hours.

So we decided to stay at the pass to see if the sun would break through and illuminate Makalu, the fifth highest mountain I the world at 8463m. Ram, Rajin and (Anna) Purna stood with us as we watched Makalu start to peak out from the left. Makalu’s knife-edge northeast ridge looked imposing, while the upper portion was the final stage of the first ascent by the French in 1955. Lionel Terray and Jean Couzy (both members of the French ascent of Annapurna in 1950) climbed from the Makalu La, across and up the north face, reaching the summit on May 15th. To the right of Makalu was Chomolonzo’s wide wall with the main 7790m summit on the left; this wall would block our view of Makalu for many days, until we could get to the west and see Makalu again. Terray and Couzy were the first to climb Chomolonzo on October 30, 1954 on their Makalu reconnaissance.

The entire party, trekkers, Nepalese and Tibetans had lunch together just below the Shao La. As I picked at my lunch, I watched the Tibetans nearby. All of them wore western style clothing with shirt, sweater and bomber-style jacket on top, western style pants, and Chinese sneakers. Interestingly their leader wore brown proper hiking boots. One of them wore a warm hat while the other five had a red piece of cloth on the top of their head to keep their hair in a bun in the back. They ranged in age from mid-30s for their leader to what looked like late teens for the youngest. On top of the provisions they carried on their backs, I could see each of them had a wide-brimmed leather hat, but I didn’t see them wear their hats at all on the trip.

With garbage bags on again, we descended a steep hillside, made fairly slippery from the drizzle. At the bottom, the drizzle turned into rain and I quickened my pace, walking down a broad valley with low-lying grass and scrubs. I had to constantly jump from rock to rock to avoid the small rivulets of water that flowed haphazardly through the valley. With the campsite in view, I soon came to the last hazard of the day, a ten metre wide river with occasional boulders and pieces of wood sticking up from the water to aid our crossing. The possibility of falling in looked only too real, when I spotted Chris on the other side resting. He advised me to come across fairly fast, jump from rock to rock, and in one section to walk in the water. I breathed deeply and across I went without a hitch. I then sat down next to Chris and waited for the others. Chris would describe to them how to get across while I took their photo. Shane and Ben made it across without incident, followed by Kumar who practically ran across. Jan was next to come, looking extremely tired. Chris implored her to focus on the rocks and relax a bit. She started across and then froze in the middle. She seemed to give us as she then simply walked in the water to get to the final section. Gerhardt made it across easily while Valerie used her walking stick to keep her balance.

We soon came to our idyllic campsite at a place called Joksam (4000m), our tents mirrored in the slow moving river beneath a hill forested with green trees. Although normally trekking groups aren’t allowed to have fires, Kumar asked Ram and Rajin to start one so we could dry out our wet clothing. The raging fire spit high into the with boots placed near the fire, while socks and jackets were hung on sticks and held near the fire, almost like melting marshmallows. The Tibetans joined us near the fire and we smiled to each other in this beautiful setting, with memories of our thefts receding from our memories.

The leader of the yak herders started to sing a song as he sat next to the fire. The other Tibetans joined in, probably singing the chorus. It was a haunting slow moving song, sung with feeling with his throat muscles straining to reach the right pitch. We all applauded wildly as they finished. Now this is what traveling is all about, I thought, meeting the local people at close distance and seeing glimpses of their lives and culture. Ben clapped the leader on the back and encouraged him to sing another song. The leader spoke to other Tibetans for a few minutes and then they all stood next to the fire. The leader started to sing, this time a faster moving song. They locked arms and started pounding the ground with their feet. We clapped along mesmerized by their singing and dancing ability. Each of them flawlessly kept to the beat and sang wonderfully. When the song ended we gave them a rousing standing ovation with yells of ‘bravisimo” and “encore” interspersed with whistles and yells.

Chris encouraged the Nepalese to sing a song. Rajin was the only one to bite and he sang an Indian pop song with great feeling. The Tibetans sang another song and then motioned for all the westerners to sing a song together. Of course we agreed, but what to sing, what to sing. Shane said how about ‘Waltzing Matilda”, Rajin wanted us to sing a pop song, maybe even Madonna, while Chris and I debated different chorus type songs. Eventually we picked Frank Sinatra’s “New York, “New York”, a great crowd pleaser in the west. The seven of us stood up to sing the song.

"Start spreading the news, I'm leaving today / I want to be a part of it - New York, New York" We couldn’t remember a lot of the lyrics so we simply sang the chorus over and over again. We linked arms and kicked our legs into the air, first left, then right. I’m not sure what the Tibetans thought of this performance, but they applauded wildly as we started to get out of sync and started kicking each other’s legs. We fell to the ground in a heap, laughing hysterically! The fire started to die and we all filed slowly back to our sleeping bags, happy with our multicultural performances.

Day 10 October 6, 1998 Trek from Joksam (4000m) to alpine camp (4500m)

The next day we ascended about 400m through the forest behind our tents and reached a high plateau with small lakes and streams high in the Kama Valley.

We stopped to rest when I looked to the west and saw my first glimpse of the enormous snowbound Kangshung Face of Everest sticking up above a black mountain. I recognized it from the many photos in Stephen Venables book, and I identified the South Col, the Hillary Step and the summit for the rest of the group. I must have suitably impressed them because they relied on me to identify all the mountains for the rest of the trek.

We continued over a couple of ridges and had lunch while we waited for the Tibetans to catch up. When they came, what looked like a negotiation or an argument between Tashi and the yak herders broke out.

We sat there for half an hour not moving at all, while they spoke. The Tibetans wanted to make camp right where we were, while the rest of us wanted to move farther. The warm feeling of the night before vanished as we insisted we move on. Tashi implored the Tibetans to move, and after another ten minutes of haggling they agreed.

They led the way for another hour before dropping our luggage and sending the yaks off to graze. We had no choice; this was camp for the night.

Day 11 October 7, 1998 Trek from alpine camp (4500m) to Hoppo (4800m)

The next morning once again dawned overcast and we continued our trek high above the Kama Chu. Ram and Rajin had to help us cross a two-metre stream on a log balanced on rocks on the two sides. From high on the ridge we could see down to a plateau just above the river called Pethang (4550m). Chomolonzo towered across the river with the Kangdoshung Glacier entering joining the Kangshung Glacier from the left. I sat down alone and had some lunch before launching across the upward slanting very loose scree slope. I wondered how the yaks would fare, but had confidence in their surefootedness.

I rounded the corner and there it was as big as life, the full view of the east faces of both Lhotse and Everest. WOW! Across the valley were the three summits of Chomolonzo.

We stopped at Hoppo (4800m), our campsite for two nights. It was set in a green meadow beside a small stream with abundant beautiful star shaped light blue flowers. We all anxiously went to bed early anticipating the next day, which would be the highlight of the entire trip. I think we all hoped for clear weather and not to suffer from altitude sickness.

Day 12 October 8, 1998 Trek from Hoppo (4800m) to Everest Kangshung East Base Camp (5050m), and back to Hoppo (4800m)

In the morning, Valerie was feeling a bit sick and decided to stay at camp, as did Kumar, (Anna) Purna and Phurba. Tashi decided to join us. Ram and Rajin would be our guides, and led us out of camp just before sunrise.

The sun quickly lit up Lhotse East Face and the three snow covered summits of Chomolonzo on our left. After an hour we came to a wide-open broad grassy spot that Ram told us was Makalu Base Camp, although I’m not aware of any climbs starting from that spot. The view to Lhotse and Everest was awesome.

We continued hiking towards the Everest Kangshung East Face Base Camp, with Pethangtse slowly separating itself from the surrounding peaks, looking very much like a perfect pyramid mountain. We really started to stretch out now. Ram was setting a very quick pace as I followed for two hours. We hiked on a fairly clear path between two hills, which blocks most of the views. After passing the British group’s camp at Pethang Ringmo, I rested briefly. I was surprised to see Gerhardt pass me by and tuck in behind Ram; I now followed in third. In half an hour we climbed the grassy slope and sat down, we were at the end of our trek at Everest Kangshung East Face Base Camp (5050m). It was 10:30, four hours after we began our hike. The weather was sunny with only occasional fluffy clouds hanging to the Everest face. The view from here was the best of the entire trek.

On my far left, the peaks of Chomolonzo were stacked behind each other. To the right was Kanchungtse (7672m, which is also called Makalu II) leading to the Makalu La and up to the summit – a brilliant view! Next in line came Chago (6860m) leading to the beautiful pyramid of Pethangtse (6738m), sometimes likened to the classic Matterhorn on the Swiss Italian border, with the Shartse Glacier lapping at its feet. The 1921 British Everest Expedition named this mountain after the Pethang Ringmo campsite where the British were camped. After dipping down to the 6177m Shar La, the ridge rises to Shartse (7502m), Peak 38 (7589m, also called Shartse II) and continues to Lhotse.

Lhotse is the fourth highest mountain in the world at 8516m. The 1921 British Everest Expedition named the peak Lhotse, which was a direct translation from the Tibetan for South Peak (of Everest). The three jagged peaks of Lhotse were brilliantly clear beginning with Lhotse Shar (8400m) on the left, Lhotse Middle (8413m) and the main summit on the right. Lhotse was first climbed by a Swiss expedition in May 1956, Lhotse Shar by an Austrian team in 1970, and it was only in 2001 that a Russian expedition climbed Lhotse and managed the difficult traverse along the 1km ridge to Lhotse Middle.

The Lhotse Northern ridge, with dangerous rocky pinnacles, drops to the South Col (8000m), the wide saddle between Lhotse and Everest, which is the highest col in the world. The Everest South East Ridge, the route of Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary’s first ascent in 1953, rises from the South Col to the South Summit, the 10m high Hillary Step and on to the summit of Everest at 8850m. The North East Ridge drops down from the summit past the third, second and first steps before meeting the extremely difficult Pinnacles. It continues to the Raphu La (6510m) rising to Raphu Peak (7045m) hidden by clouds, and finally Kartse (6550m) and Karpo La (6084m).

The East face looks frightening from this close-up view. Especially terrifying is the drop straight down from Lhotse Shar to the glacier with avalanches keeping the face almost clean of snow. Clearly visible on the snow covered face was Stephen Venables’ ascent route, following the rocky headwall, traversing to the left and climbing out onto the South Col before joining the classic route to the summit.

The three of us just sat there admiring the view for over an hour and a half when Chris joined us. He told us he had altitude sickness and had stopped at the British camp for a rest. I was really impressed by his willpower to continue his hike even though he looked just awful. I looked around for a small rock in the shape of a pyramid as a suitable souvenir. Ram noticed what I was doing and kept giving me rocks to look at. After another half an hour clouds started to cover Everest’s face, so the four of us decided to head back. We walked to the British Camp and were surprised to meet Shane, Jan, Ben, Rajin, and Tashi sitting and talking to the British Camp Nepalese.

We recommended they take the half hour walk to our vantage point, but they declined since they were all feeling the effects of the altitude, the four-hour hike to get there, and knew they’d need another three hours to get back to camp. The British Nepalese crew served us some milk-tea and cookies, and told us that Stephen had led the trekkers onto the Kangshung Glacier, and were attempting to get to Advanced Base Camp at the foot of the Kangshung Face. It was getting late, we still had a three-hour hike ahead of us, so we said goodbye.

Silently we all fell in line behind Ram for the long trek back to our camp. The hike seemed to go on and on, after such a delightful and tiring day. Ram stopped to pick up a hollowed out animal skull that we had spotted on the way up, but after carrying it for 15 minutes abandoned it because it was too heavy. Meanwhile, Gerhardt picked up a bark-covered walking stick and carried it back to camp. Eventually we reached camp, had a quick dinner, and fell asleep. This was simply one of the best days of my life.

Day 13 October 9, 1998 Trek from Hoppo (4800m) to Pethang (4550m)

I was up early the next morning, but scattered clouds shielded part of the Everest Kangshung East Face. The Chomolonzo wall, however, was quite beautiful with pinkish fog silhouetted along the bottom and the top glistening white in the early morning sun. As Ram prepared breakfast, the clouds lifted to reveal the Everest-Lhotse wall in its early morning splendor.

We retraced our steps, carefully crossing the 45-degree scree slope. We camped overnight at Pethang, next to the Rabkar Chu just before it joins the Kama Chu.

Day 14 October 10, 1998 Trek from Pethang (4550m) to base of Langma La (4800m)

The next morning, we leisurely got ready to leave camp, and before we knew it, the British group passed us and started the ascent to the base of the Langma La. I fell in behind Stephen Venables and started as well.

We rested on a slope, with brownish shrubs all around. I sat down with Chris and chatted amiably with Stephen. He told us the group had a lot of trouble on the Kangshung Glacier and only made it half way to Advanced Base Camp. He really wanted to get there, but honoured his role as trek leader by turning around and leading them safely back to base camp. He was really impressed with Bill Norton, who kept up with the much younger trekkers and was always climbing some side crag whenever they stopped.

As we started again, the two groups intermingled, and camped together at the base of the Langma La (4800m).

It was still fairly early, so I walked the short distance to the Shurim Tso lake, its turquoise water hemmed in by the rock headwalls that lead to the Langma La. The clouds rolled in quickly obstructing most of my view, so I very slowly returned to civilization and some tea and cookies in the mess tent. I could see the mostly white Rabkar Glacier taking a 90-degree turn as it petered out across from our camp.

Day 15 October 11, 1998 Trek from base of Langma La (4800m) over Langma La (5330m) to Lhatse (4900m)

As we broke camp the next morning, I gazed above the Rapkar Glacier to the top of the Lhotse-Everest east faces, bright white in the early morning sun. Ben and I left first and walked along the edge of the lake, thinking it was a short cut. Before long, we were clambering over enormous boulders, many a couple of metres high. When we rejoined the main path, Chris was already ahead of us - so much for short cuts. I picked up my pace to try and catch Chris, but whenever I rounded a bend, the farther ahead he was. I looked back and could see that the two trekking groups had intermingled on trail.

Up and up I climbed the steep rocky slope, and finally arrived at the top, the Langma La. Chris took my photo next to the chorten and prayer flags that mark the high pass, with a rock identifying the altitude, 5360m. I took Chris’s photo and then we sat down to wait for the others to arrive. We stared across at Makalu’s northeast ridge leading to the summit, just barely peaking out from behind Chomolonzo’s three summits. Clouds already had rolled up the Kama Valley and now partially obscured the lower parts of the Lhotse-Everest east faces.

The others arrived, and we all sat there admiring the view, taking in our one last chance to see this magnificent panorama. Sure enough, after Bill Norton arrived, I saw him climb up the rocks on the left side of the pass. “He loves rock climbing”, Stephen reiterated. Rajin’s beard was now fully grown as he sat down puffing on a cigarette. Tashi sat next to me - still looking exactly the same as the first time I met him in Zhangmu. We were still sitting there when we heard the tinkling bells alert us that the yaks and Tibetan yak herders were coming. After reaching the top, they immediately continued starting down the other side of the pass.

Kumar told me it was another three hours to our camp that night. So, around noon, after sitting on the pass for over two hours, I decided to continue; besides, the clouds were shrouding most of the mountains as well. The rocky path plunged in zigzags before flattening out. The path again plunged on a slippery scree slope to a one kilometre long beautiful green lake flowing over the lip to a place at the base of the pass. This place was aptly named Lhatse (4900m), Tibetan for ‘the place below the pass. As I continued, I could see both camps were already set up about 500m apart, well below the trail. I kept my eyes on Chris, depending on him to lead me to the correct tents. About two and a half hours after leaving the pass, I strolled into camp, gladly accepting a hot milk-tea from (Anna) Purna. Before long it started to drizzle and I retreated to our tent.

Day 16 October 12, 1998 Trek from Lhatse (4900m) to Kharta (3690m)

We continued down the uninhabited valley the next day walking alongside the little river flowing from the lake I had passed the previous day. There was supposed to be a good view of Kangchenchunga from the valley, but it was topped with clouds. We all smiled as we entered the first village we had seen in many a day. A woman was drying enormous clumps of hay on the top of an animal enclosure, while children ran up to us. Once again, Jan was smiling, blowing bubbles to delight the kids.

We rejoined the Karta Chu and walked slowly along, not wanting the trek to end. The truck driver and three landcruiser drivers waved as we walked back to our first campsite.

Day 17 October 13, 1998 Drive from Kharta (3690m) to Rongbuk Monastery (5000m) and Everest North Base Camp (5200m)

We had breakfast the next morning out of doors as the crew broke camp. I watched Tashi pay each of the Tibetans and then asked Tashi to ask them if they minded me taking their photo. They were only too happy to oblige as they posed, smiling broadly. I’m sure they were happy to get back home, and to bring some extra money to help their struggling families.

We waved goodbye and jumped into the landcruisers to start our drive to Everest’s North Base Camp, near the Rongbuk monastery. Some of the local people knew where we were going and asked Tashi if they might ride in the back of the truck, on a pilgrimage to the monastery. In they jumped and off we all went. This time we met oncoming traffic; in fact it was several army vehicles. We backed up the one-truck wide road, and waved the army trucks to pass us. They pulled out to the very edge of the road high above the Phung Chu River and slowly passed us. We stopped again at Peruche and I enjoyed my first Pepsi in a couple of weeks.

We stopped for lunch near at the edge of the west branch of the Dzakaa Chu River. I sat down to wait for Ram to get the lunch ready when I looked over the top of a brown hill and saw the tip of Everest. We all sat down to eat our lunch, including the pilgrims. I looked toward the west and saw what looked like a cowboy heading our way. As he came closer, I could see he was a local Tibetan on a donkey.

We continued along the rough rocky road and stopped at the Rongbuk monastery (5000m). The Rongbuk monastery set a spectacular foreground for the classic photo of the North face, with its umbrella and spire-topped chorten connected to the ground with flapping prayer flags. When the British Expeditions came through here in the 1920s, this was a thriving monastery of 500 monks and nuns, but it was destroyed in the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and is now being rebuilt.

The snow-covered north face of Everest gleamed brilliantly white in the early afternoon sun, not a cloud in the sky. I strained my eyes to catch the features of this most beautiful side of Everest.

I could see how the jagged Pinnacles had stopped so many expeditions over the years who attempted the northeast ride. The Japanese finally climbed it in 1995 after over 20 Sherpas had fixed almost the whole route with fixed ropes. The normal route from the north col joined the northeast ridge just past the Pinnacles. I could clearly see the famous first, second and third steps leading the normal route to the summit. To the left of the summit area was the Great (Norton) Couloir reached by Edward Norton in 1924. To the right of the summit was the Hornbein Couloir, named after Thomas Hornbein. Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld, members of the 1963 American Expedition, climbed part of the West Ridge before crossing onto the North face and climbing through the couloir, that now bears his name, to the summit. They then descended the route of the first ascent, bivouacking high on the Southeast ridge. Below the couloirs lay the snowy area called White Limbo by the Australians who climbed the North face direct in 1984.From this vantage point I could see full length of the 6.5km long West Ridge. From the summit, the West Ridge plummets at an angle of 45 degrees before meeting the less steep long West Shoulder that drops just out of my view to the Lho La. The Rongbuk Glacier was clearly visible lapping at the foot of the North Face. Two other mountains blocked part of the view: Changsheng (6977m) below the Pinnacles and Changtse (7583m), named by the 1921 British Expedition from the Tibetan for North Peak, directly below Everest’s summit.

We would be camping in a small grass enclosure next to the monastery. But since it was still early and so sunny, Kumar suggested we all go to base camp in the afternoon. We all readily agreed and jumped in the landcruisers for the half hour drive to base camp, about six km from the monastery. I walked alongside the Dzakar Chu River and threw in a few stones as I once again thought about my son Peter.

I came to some monuments to the dearly departed who died trying to climb Everest. A black rock sitting on top of a small chorten stated “Marty Hoey 1957-1982”. Marty was the American climber whose waist harness came undone high on the North Face, and fell to her death. Lying upright next to the chorten was a beautifully carved piece of light coloured rock, brought by Marty’s mother to commemorate her life amongst the mountains. A simple rock was inscribed “In Memory of Peter Boardman and Joe Tasker May 1982”, two of the finest British mountaineers of their time, who died on the second Pinnacle attempting to climb the Northeast ridge.

Just behind the monuments, I climbed onto the terminal moraine of the Rongbuk Glacier and trekked along the rough up and down trail, the tip of Nuptse coming into view behind Everest’s West Shoulder. After an hour, the going got very tough, so I decided to play it safe and stopped near some large glacier pools of water. About fifteen minutes, Chris, Ben, Gerhardt and Valerie joined me to enjoy the view. The shadows of the coming evening signaled us to head back to our camp.

The British had now arrived and were camped just down from us. They planned to visit base camp the next morning.

I stood in the –10C temperature and watched the whites of the afternoon sun change to the yellow, pinks and reds of sunset. Awesome! While I was watching the sunset, the others had gone to the lodge run by the monks and had a few beers. They rejoined me in the mess tent for dinner. After dinner was over, AnnaPurna brought in a special chocolate cake he had baked to celebrate the end of the trek. Tomorrow Ram, Rajin, Phurba and Purna would be heading back to Kathmandu. We thanked Purna for his kindness and devoured the cake in minutes.

When we were alone again, Jan brought up the topic of giving the Nepalese crew their tips in the morning. Since this was my first organized trek, I deferred to Jan to explain what was the appropriate protocol. We pooled our money and then decided as a group how much to give each crew member.

Day 18 October 14, 1998 Drive from Rongbuk Monastery (5000m) over the Pang La (5250m) to Shegar (4350m)

I was up early the next morning, camera at the ready to capture the sunrise spectacle. Everest stood white against the white sky. The sun hit the Pinnacles, the summit and Chantgse, turning them slightly yellow, but for only a minute. The light then changed to a flat white, so I went for breakfast. The sunset was far better than sunrise.

After breakfast the camp was taken apart and put on the truck. I asked Kumar to gather everybody around and that I was going to give them their tips. “First of all I’d like to thank you all for a safe trek.” I started. “We came here to see the east face of Everest, and we saw it perfectly clear. We also wanted to see Lhotse and Makalu and we saw them perfectly as well. Finally, we wanted to see the North Face, and yesterday was perfect. Thank you all very much.” We all clapped our hands, whistled and yelled. “I have the honour of giving you some tips to thank you for your hard and dedicated work in supporting us on the trek of our lives.” I said.

After giving them their tips, we took group photos with each person’s camera. Phurba, Purna, Rajin and Ram jumped in the back of the truck, and we waved goodbye as they drove down the road. They’d be in Kathmandu by nightfall, and preparing for their next trek.

Tashi led us though the door and into the courtyard of the Rongbuk monastery. We looked around the monastery, which was still being repaired. We then jumped in our landcruisers and started the drive away from Everest. After stopping for lunch, we ascended to the Pang La and stopped in perfect weather.

I stood there silently, listening to the prayer flags flapping in the wind. I admired the view from Makalu on the left to Everest and Lhotse in the centre and Gyachung Kang and Cho Oyu on the right. Magnificent!

We continued down the other side of the Pang La, passed through an Army checkpoint and rolled into the Chinese Qomolanga Hotel in Shegar (4350m), also called New Tingri. The hotel was a large square-shaped building with a large courtyard in the middle. The dinner hall on one side and a bar on the other flanked the expansive lobby. Chris and I went to our room, which had two western-style twin beds, and a bathroom with a western-style sit-down toilet and what looked like a bathtub with shower. I tried the water - no luck. I went to the hotel store and looked around: cigarettes, matches, cookies, Coke and Water, and ahh, there it is beer. I bought a couple of large Lhasa beers with the slogan ‘beer from the roof of the world’ on the label, and returned to the room. I turned on the TV and watched a few minutes of a Chinese program while Chris and I drank our first beers in weeks.

Before dinner, I went to the bar and enjoyed another beer with Jan and Shane. I sat down at 10-seat round table to have dinner, starting off with another couple of beers. I looked around the dinner hall and looked longingly at a large painting of the North face of Everest. Tashi sat with the drivers and had a coke. The British group was already here, and would be on the same daily itinerary as us until we got to Lhasa. I don’t remember much about the dinner, but I’m sure it was totally average. Our itinerary had us going to the Shegar Fort the next morning, but Kumar suggested we visit the Sakya Monastery instead. We all quickly agreed.